Local veteran pursues a life of art, film and music after military service

Whether it’s his fluency in multiple languages, from Arabic to Mandarin Chinese, his remarkable ability to sing, or the fact that he has visited and lived all over the world, Port resident and veteran Zaque Harig Townsend, has so much more to offer.

He served in the Marine Corps during the Iraq War, working in civilian affairs while deployed to Afghanistan. As one of the few servicemen able to speak Pashto, one of Afghanistan’s two native languages, Harig was key to communications between Afghan locals and Marines, as well as interception and translation Taliban radio frequencies.

While Harig’s time in military and educational pursuits has taken him across the planet, his story begins in suburban North Chicago.

THE FORMATIVE YEARS

Harig grew up in the Chicago suburb of Northbrook where he discovered his first muse through his local church choir.

“I had a busy childhood with a lot of traditional church, community, family structures and many extensive facilities in the area,” he said. “I was also in a professional children’s choir…that’s what really sparked my love of languages.”

He was exposed to the linguistic world through singing, as the choir learned new songs in a multitude of different languages every two weeks.

Eventually, he traded the Windy City for Washington, D.C. while attending George Washington University.

There, Harig expanded his knowledge of the language, learning Mandarin and developing his fluency in Arabic.

“I found Arabic to be by far the most difficult because of the grammar. I didn’t think Mandarin was that bad, but it’s a tonal language,” Harig said of his experience learning two of the languages that many consider the hardest for Westerners to master.

JOIN THE MARINES

While enjoying his college time, Harig took a year off to recalibrate, which eventually led to him joining the Marines.

“I knew I had a lot of ambitions and wasn’t yet the man I needed to be to do the things I wanted to do, so it just occurred to me in one day to become a Marine,” he said.

“It never crossed my mind to join the military. I’ve never played shooting video games, I didn’t know anything about it. I knew it would be difficult, that it would alleviate some of my asperities and would make me more resistant.

During this time, Harig was addicted to the hit action show “Alias”, which encouraged him to pursue a reconnaissance role in the military.

“At the time, I thought I wanted to be a spy; I thought I wanted to work for the CIA,” he said. “I was captivated by the TV show ‘Alias’ and Jennifer Garner’s character, Sydney Bristow.”

He soon came into contact with the Marine Corps, signing a contract the same day as he prepared to ship quickly for boot camp.

“I told my parents a week later, and I was in training camp a week later,” he said.

After several frustrating months of missing reconnaissance missions, switching to infantry, and finally choosing civil affairs, Harig deployed to Afghanistan.

“The first three months were almost daily firefights and calls for air support,” he said. “It was surreal and intense. I had to interpret for debriefings of informants, interrogations of detainees, and sometimes going into battle with an earpiece listening to live Taliban radio frequencies.

During their stay, Harig and his comrades in arms had to deal with sub-zero temperatures. And scorching days, too, where it reached up to

140 degrees in summer.

“It was so stressful and the pressure was so high…it was very difficult,” he said of his deployment. “Then I came home and had a really hard time adjusting.”

WAR RECOVERY

Faced with the trauma of his wartime, Harig left the United States for a change of pace in the lush farmlands of northern Italy.

“It was an amazing experience actually, the whole community welcomed me,” he said of his time as a farmhand.

His singing background came in handy at the Italian Count’s (farm owner) birthday party, when Harig serenaded revelers with Eagles’ “Desperado,” as listeners sang along swinging their arms in unison.

He spent time in Switzerland and Chicago for college, but continued to struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder and eventually traveled to Ireland to pursue an international development program and join an Irish class choir. world.

While enjoying international development, Harig realized that his true passion was art.

“I decided to uproot my life to Ireland because in this contemplation of life and death and ‘What are we really doing here’ I hadn’t prioritized art. My art dreams were on a shelf,” he said, adding, “It would have been cool, but I didn’t feel like it would feed my soul or allow me to live to the fullest.”

Harig returned to DC with the goal of honing his film, music, writing, and other art forms, but a familiar opportunity presented itself with recognition in the military, but this time he got it. Refused.

“It was a very difficult decision. It was the last time I turned away from all this seduction of the intelligence world, I think it would have ended up making me someone I didn’t want to become. , which is why I fully embraced the art at this point,” he said.

His first major artistic endeavor during this time came after buying a Ford pickup truck and planning to venture across America in search of gripping stories.

After raising $20,000 for the project, he traveled to Washington State and began filming a collection of interesting, informative, weird, and funny stories on video media.

Harig has covered anything from an Anacorte couple’s whale-watching activity to a drunken flash mob in Ellensburg to a Benedictine monk in Oregon.

While the wide variety provided great content, Harig then focused on post-9/11 veterans and their trauma recovery experiences.

PANDORA’S BOX

After a friend encouraged him to sort out his own feelings of deployment, Harig went through a kind of depression after revisiting a past trauma he had been pushing away for years.

“My only structure was this weekly therapy session at a vet center in California. I kind of made it to myself; I was curious to see if there was anything, so when I opened Pandora’s box, I did something I couldn’t undo,” he said.

After forcing himself to read all of his deployment notes and letters, it brought back memories and flashbacks that he had kept in mind from his time in the Middle East.

“All the triggers got worse and then suddenly, when I was relatively well a few days before, I had hyper-vigilance all the time, panic attacks, painful anxiety, nightmares, memories of things that I had forgotten, flashbacks. It was like I was living a TV episode. It was very difficult and the therapy process was slow.

“It wasn’t until I was robbed and someone smashed my van window and stole my backpack with every film, every photo, every writing, every creative thing I had worked on these years, has been ripped out of my life,” he added.

Back in Chicago, Harig recuperated with his parents for a time.

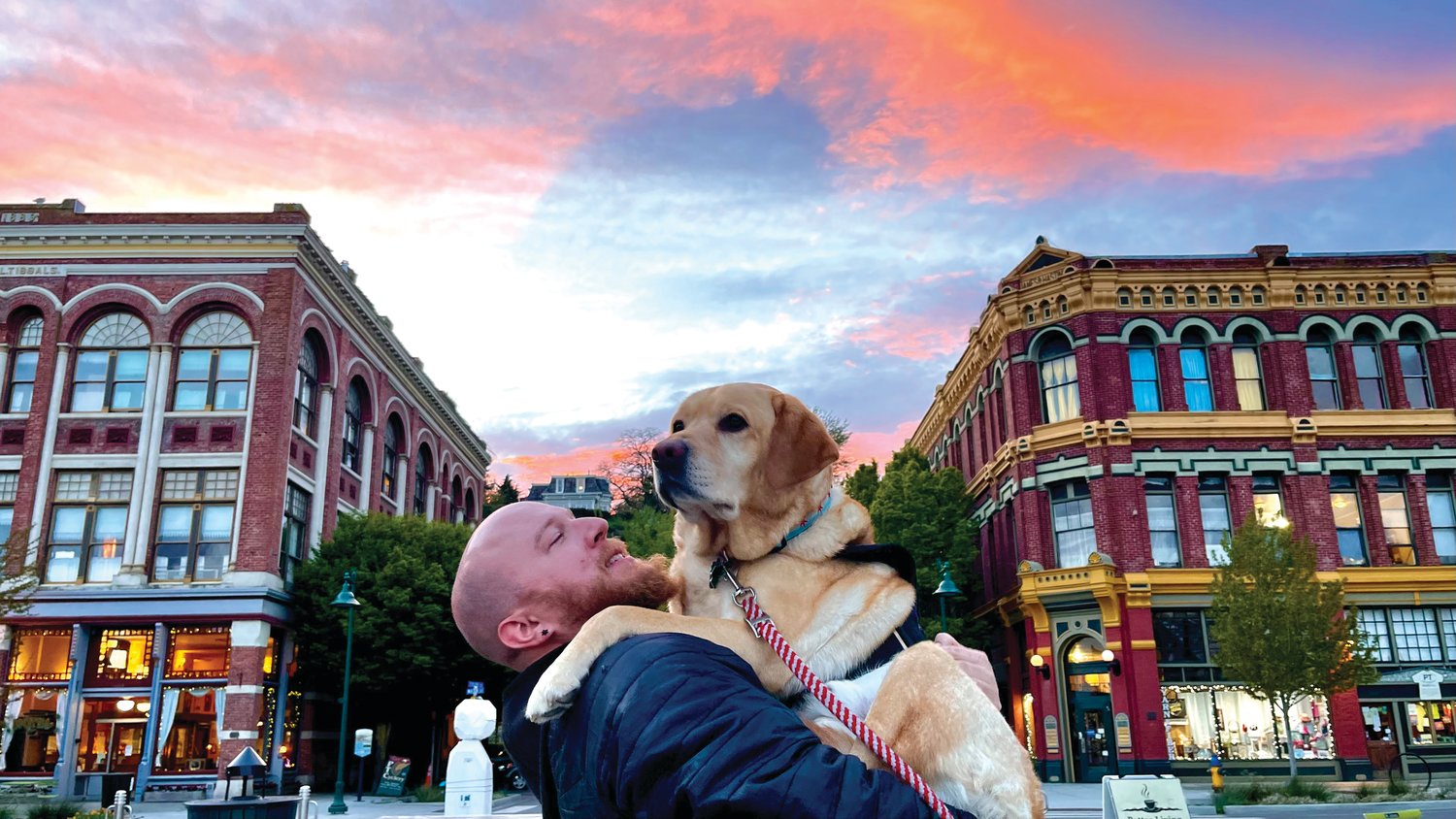

“I was basically housebound and messed up for about a year, and that summer I got Freedom, my service dog, and it was a gradual process of reintegration,” he said. .

After a while, his passion for film was rekindled when he finally graduated from film school and decided to go to Port Townsend, a haven he remembered after visiting a friend on his van adventure.

FIND A HOUSE IN PT

“Back when I graduated, I always remembered the one time I visited Port Townsend about five years ago, and I thought, ‘This is the best place to be. I went. I have never felt more at home than during this weekend,” said Harig.

With Freedom (the service dog) by his side, he arrived on the Olympic Peninsula and joined the Port Townsend Film Festival as an intern before working his way up to director of marketing and development.

Thinking back to when he was deployed, Harig shared his thoughts on the transition from soldier to civilian.

“Everyone is so real. I think for this brief window of time [while deployed] we have all become the purest, unfiltered version of ourselves and exist exactly as we are, while some of us were in our last lives or had all of our limbs,” he said. . “You’ll never forget what it was like to live so completely stretched out, and that’s what’s so hard about transitioning.”

“The sacrifice wasn’t getting shot; the sacrifice is living your best, truest, fullest life for a short time and having to give it all up and play the game again,” he added.

Sharing wise wisdom on the ups and downs of adventure, Harig said: ‘You could be invited to an earl’s birthday party with all-organic food produced by his on-site chef while everyone famously serenading the Earl with ‘Desperado,’ or you could end up being drugged and left on the side of a mountain in Switzerland to die in the snow with no money, phone or coat.

Comments are closed.