Open schools, with an emphasis on the early years

[ad_1]

Even before the pandemic, India faced a serious learning crisis – with nearly 50% of grade 5 students in rural India unable to read even at grade 2. The pandemic and 16 months school closures have almost certainly made matters worse. A recent study from Azim Premji University estimates that 92% of children in grades 2-6 have lost their language skills and 82% have lost their math skills. The costs of those 16 months of school closures are likely to be lasting and could potentially frighten an entire generation of Indians.

For example, in a recent study on the aftermath of the 2005 Pakistan earthquake, economist Jishnu Das and colleagues found that just four months of school closures resulted in learning losses of nearly two grade levels. over time. How could four months of school closure mean two years of lost learning? One possibility is that the teachers continued with regular education at the school level and that the children who had fallen behind could no longer follow. In other words, missing even four months of school not only hurt the level of learning, but may have permanently reduced the rate of learning in school, resulting in a much greater cumulative learning loss. over time.

Another key idea was that learning losses were very uneven; children of educated mothers were able to compensate for school closings, but children of uneducated mothers were particularly affected. Thus, the trade-off between the increased risk of infection resulting from the opening of schools and the loss of learning resulting from their closing is likely to vary greatly by socio-economic status. For educated parents with access to technology at home (who dominate public discourse), it might have made sense to teach their children at home. But, for tens of millions of children whose parents have not been educated and whose access to technology is limited, the cost of school closures has likely been much higher.

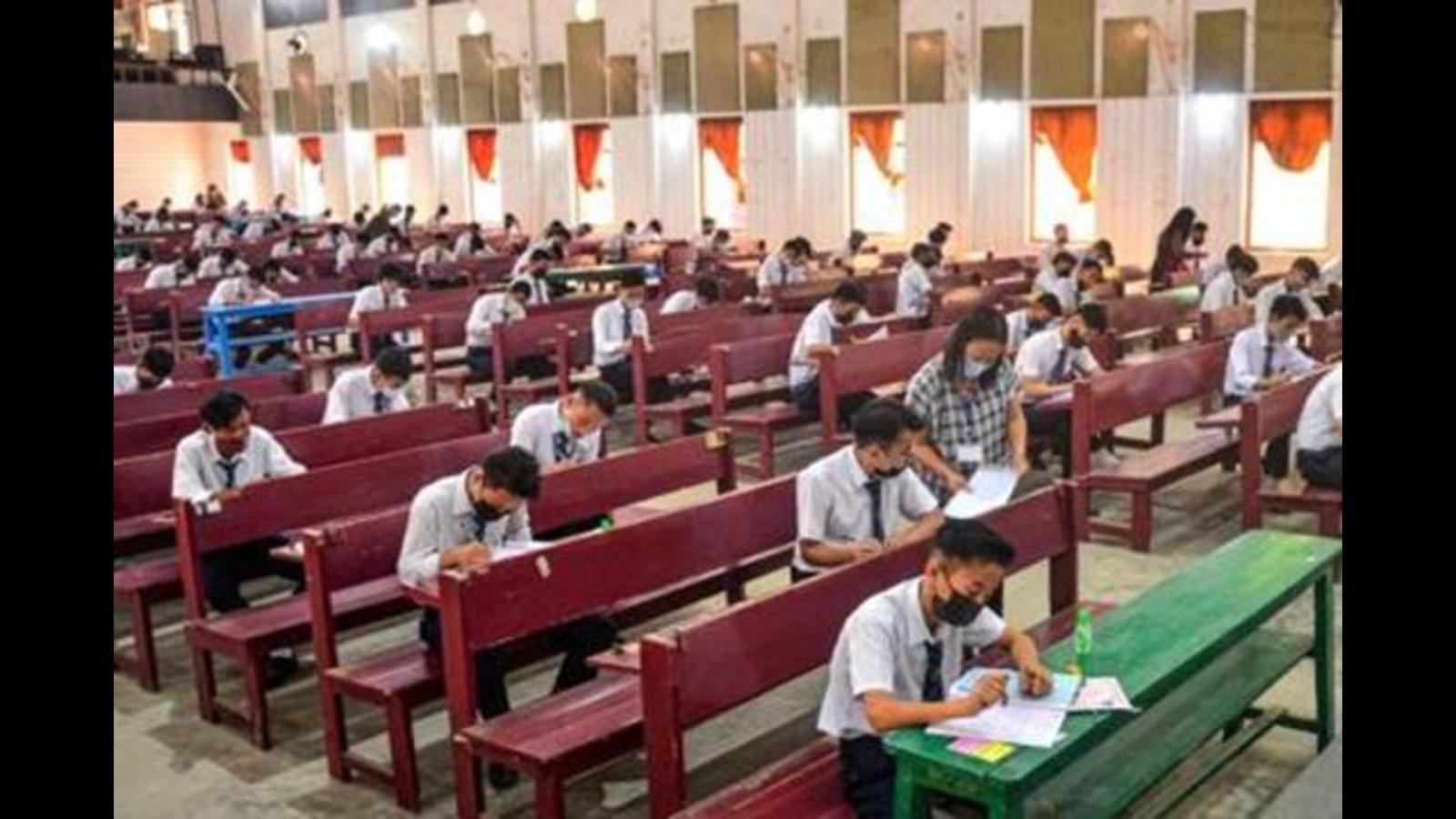

Thus, the most important task of the new Minister of Education is to ensure the rapid but safe opening of schools. The minister said that the implementation of the new National Education Policy (NEP) is its main objective, and the NEP correctly identifies that the highest priority for our education system should be to provide basic literacy and numeracy (FLN) universal. However, that goal will be stillborn if schools remain closed.

Fortunately, we now know enough about Covid-19 to be able to safely open schools. Entities such as UNICEF, UNESCO, the World Bank and the Lancet COVID-19 Commission Indian Task Force have all issued detailed recommendations to guide efforts to reopen schools while minimizing the risk of infection. . When schools reopen, we should aim to implement these recommendations and minimize health risks. In addition, I present six key principles to ensure that reopening schools can mitigate learning losses.

First, since school education is a state matter, the decision to open schools and the modalities for opening them should continue to be left to the states. However, the central government should provide guidance, technical support, and financial resources to make it easier for states to do so.

Second, while the instinct of many officials is to open grades 9 to 12 first due to board exams, the top priority should be to open grades 1 to 5 to ensure universal mastery of skills. fundamental as prioritized by the NEP. A large body of evidence points to the importance of the early years in human capital formation and our priorities for opening schools should reflect this evidence. Additionally, while older children can still absorb online content, thanks to self-study and virtual groups, in-person interactions with teachers are much more important at a younger age.

Third, it is essential to pay attention not only to the opening of schools, but also to the modification of pedagogy to take into account the 16 months of school closures. Simply teaching the textbook can be ineffective if children fall far behind grade standards. On the contrary, schools and teachers should be encouraged to focus less on the textbook and more on basic reading and numeracy skills and to address learning losses.

Fourth, we should move from the rigid “regime-based†central government funding model to a more flexible model with greater spending autonomy for states and districts. For example, an innovative idea recently proposed by Rukmini Banerjee is that funds from the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) be used to pay daily fees to young people in 10th and 12th passes in villages that provide remedial classes for help children compensate for learning losses. . More generally, since we are in unknown territory, we will have to innovate, iterate and react quickly according to the different realities on the ground across the country.

Fifth, school openings should not be treated as an all-or-nothing decision. It is likely that there are substantial benefits even from a partial reopening of schools (for example, when 50% of students in a class attend all alternate days). This will allow social distancing while allowing students to engage with teachers and peers.

Finally, given that private schools account for almost 50% of school enrollment in India, they should also be allowed to open under the same guidelines as public schools.

Media and political attention during the pandemic naturally focused on the immediate tasks of saving lives by providing beds and oxygen. Yet the greatest long-term cost of the pandemic may be borne by our children. As the second wave of Covid-19 recedes and we slowly try to restore some semblance of normalcy, one of our top priorities as a country should be to open safe schools.

Karthik Muralidharan is Professor of Economics at the Tata Chancellor at the University of California at San Diego and Global Co-Chair of Education at the Jameel Poverty Action Lab (JPAL). Vishnu Padmanabhan contributed to this piece.

Opinions expressed are personal

[ad_2]