Some school districts in rural San Diego county can’t pause with COVID

PINE VALLEY — In rural school districts like Mountain Empire in San Diego County, COVID is hitting especially hard.

A triple whammy of pandemic-related issues — insufficient staff, frequent absentee students, lack of reliable internet — has hit virtually every school, but its impact is compounded in rural schools by the distance and isolation they face. clean.

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

Just ask Mountain Empire Superintendent Patrick Keeley. For two months this winter, he was named principal and vice-principal of the only high school in his district. This is because the principal and deputy principal were recruited from schools in large cities.

It’s hard for him to find new employees, he says, not just because of COVID, but because he has to convince job applicants that it’s worth driving 30 miles or more a day in the hills to work in their schools.

Mountain Empire Unified School District superintendent Dr. Pat Keely visited one of his district’s elementary schools on Tuesday, February 1, 2022 in San Diego County, California.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

“When you talk about rural education inequities, we don’t have the resources,” Keeley said. “I really think rural education has been affected, and it regularly is, by larger events, whether it’s COVID, recessions, any of those things.”

The state recently reported that 35% of Mountain Empire students were chronically absent last year, meaning they missed at least 10% of the school year. This is worse than the 22% who were chronically absent two years earlier. This is an increase largely related to COVID.

Many schools saw higher than usual absences last year, when school sometimes meant logging onto a computer at home, rather than coming to a campus. But even when school doors have reopened, some rural schools are still struggling.

” Let’s be realistic ; this has been difficult for all schools in California, but… these rural schools have very complex transportation, connectivity and staffing issues. It’s very, very difficult,” said Tim Taylor, executive director of California’s Small School Districts’ Association.

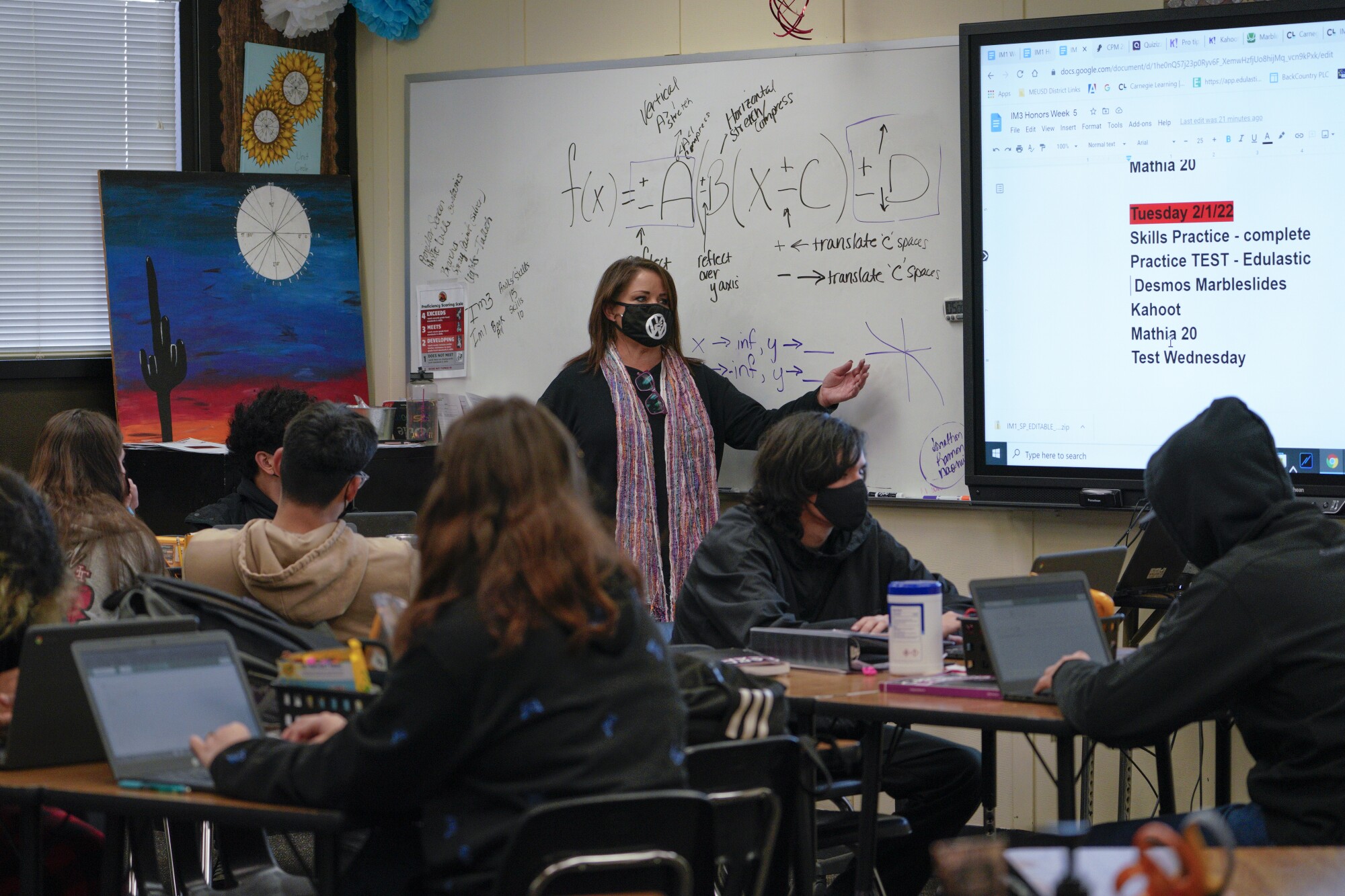

A student in an honors math class works on today’s assignment at Mountain Empire High School.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Mountain Empire already had attendance issues before COVID. It is a sprawling 660 square mile district, with seven schools serving 1,700 students. The eastern side of the district borders the Imperial County deserts and its southern side borders Mexico.

It has eight bus drivers – two less than the district needs – and 10 van drivers who transport the 90% of students who rely on buses to get to school.

Mountain Empire students are diverse – they live on farms, trailer parks, housing estates, and three Indian reservations served by the district. Some families have moved here for the open spaces and quiet; others have moved here because they cannot afford to live in the city or in the suburbs down the hill.

Many Mountain Empire students have high needs. Three in five come from low-income families and about one in three is learning English.

But many of the reasons for their absences were beyond the control of students and schools.

Children line up by assigned class for the start of the school day at Campo Elementary School.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Chief among them last school year was the lack of reliable internet. Students were supposed to learn online, but there are gaps in data coverage across the district, and some areas are only served by small data providers.

County school officials offered Verizon Internet hotspots for school districts to give to students who did not have Internet access.

But in Mountain Empire, due to topography, Verizon only works along major roads, so the district has purchased its own AT&T hotspots, costing the district about four times as much per student, said Keeley. But even AT&T doesn’t cover all parts of the district.

In October 2020, Mountain Empire reopened its school campuses for part-time in-person instruction, but it has struggled to stay open consistently.

The following month, the district closed for two weeks as it had to quarantine nearly all of its transportation service due to COVID cases. This was a problem because the vast majority of students depend on buses to get to school.

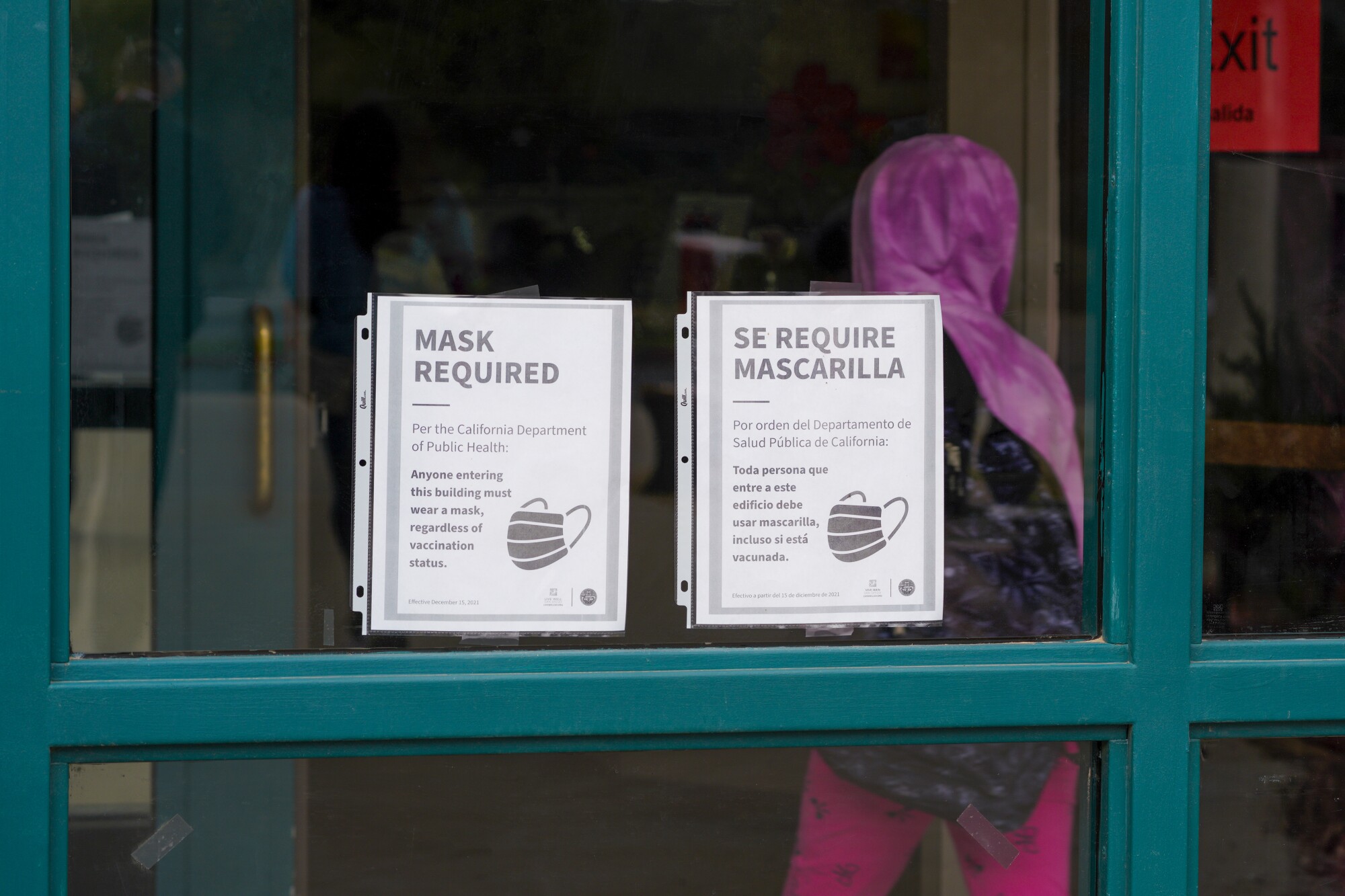

Sign posted at all school entrances in the Mountain Empire Unified School District stating that anyone entering the building must wear a mask, as required by the California Department of Public Health.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

The district returned to distance learning and had planned to reopen after the Thanksgiving break. But four days of high winds and power outages forced the district to remain closed, Keeley said.

Mountain Empire has returned to remote learning whenever it has had to shut down unexpectedly, Keeley said. Each time, however, it risked having students absent due to connectivity issues, he said.

Not only was it difficult to get children to school, but it was difficult to find enough adults.

Job applicants declined interviews the district attempted to arrange once the applicants realized how far away the Mountain Empire schools were.

Keeley can’t offer to pay employees as well as large school districts. This is partly because 7% of the district’s budget, or about $2 million, automatically goes to bus transportation.

Students work on their graphic arts homework at Mountain Empire High School.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Most school districts charge parents for the bus, but Mountain Empire doesn’t because many of its students come from low-income families, Keeley said.

This means Keeley has less money to pay his staff. The starting salary for teachers at Mountain Empire is $47,377, which is $3,400 less than what San Diego Unified offers. Mountain Empire only pays substitute teachers $150 a day, compared to $250 for San Diego Unified.

Mountain Empire has approximately nine substitute teachers for the entire district of 110 educators. Keeley ideally wants at least 20 to 25.

“It’s always been a challenge here with the subs, but this is unreal,” he said of the pandemic.

It’s not just about new employees; the district lost other opportunities to larger districts, Keeley said.

Mountain Empire Unified School District Superintendent Dr. Pat Keely visited and spoke with Campo Elementary School staff while watching school children arrive at school.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Earlier this year, Keeley hoped to strike a deal with an organization that would offer after-school and summer programs. But the organization said it would not be able to work with Mountain Empire because it had a bigger deal with a larger school district.

Amid the disruption, Mountain Empire students’ performance on standardized tests plummeted last year.

About 71% of its students failed to meet state standards in English and 85% failed in math. That’s worse than in the 2018-19 school year, when 63% failed to meet English standards and 76% failed in math.

To improve academics, Keeley said the district is focusing on reading in the early grades by staffing each elementary school with a literacy specialist.

“I wouldn’t call it learning loss. It’s just that we need to create interventions to close the gaps and catch up with students,” said Mona Noren, principal of Campo Elementary School in Mountain Empire.

Despite the challenges, says Keeley, her students are resilient. After all, many get up early and walk out into the cold to catch the 6 a.m. bus and make the hour-long trip to school.

Schoolchildren arrive at Campo Elementary School Tuesday, Feb. 1, 2022, in San Diego County, California.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

And every weekday morning, Keeley drives more than 30 miles from her home in Santee to Mountain Empire. He grew up here and went to school here and speaks fondly of the neighborhood.

It describes how, in the fall, families gather to watch Friday night football at the high school stadium, which is framed by a wide backdrop of mountains and open skies. Families here trust principals and teachers, he said, because they’ve been in the community for decades.

“This school meant a lot to me when I was a kid, this district did that,” Keeley said. “So to try to come back, to try to be a part of it, to help improve and help improve the lives of the kids here in any way we can, is pretty important.”

Comments are closed.